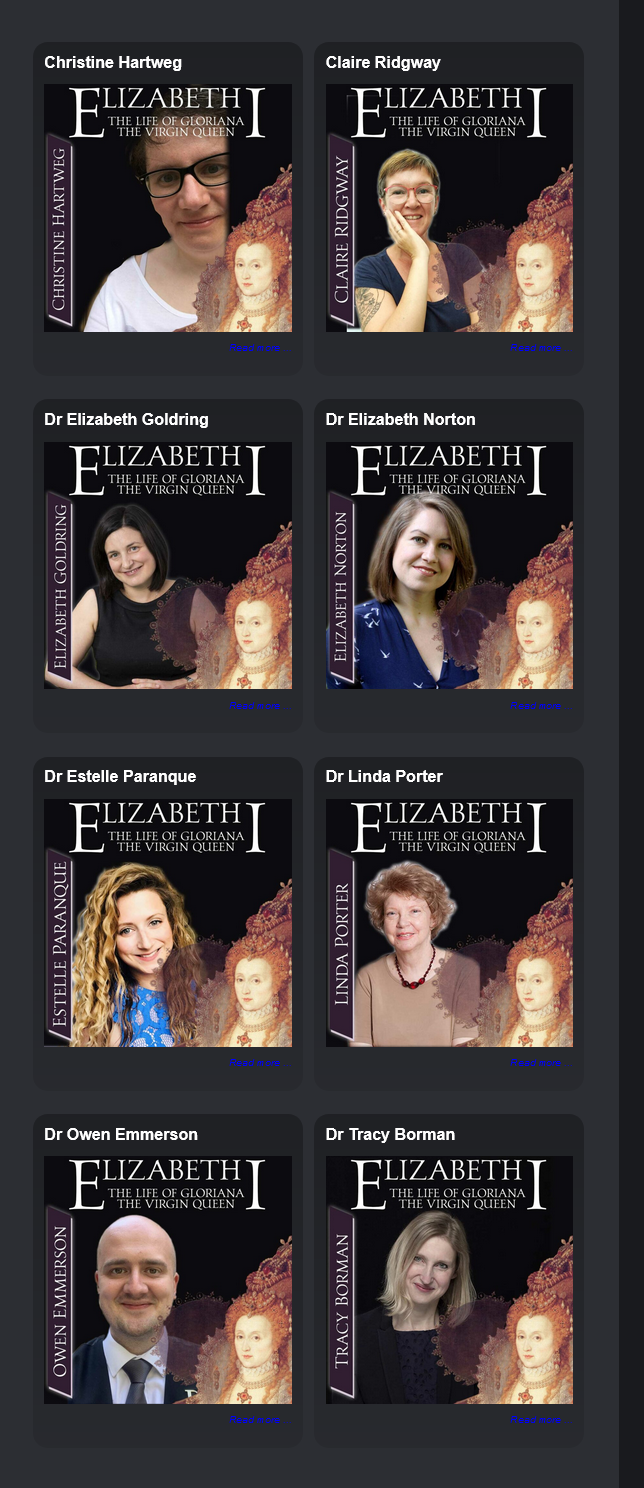

Just a note that in the summer of 2022, I was honoured to be part of Claire Ridgway’s Elizabeth I online event. We had an in debth talk via Zoom about Amy Robsart. Meanwhile the event is closed, but it was a wonderful experience.

Just a note that in the summer of 2022, I was honoured to be part of Claire Ridgway’s Elizabeth I online event. We had an in debth talk via Zoom about Amy Robsart. Meanwhile the event is closed, but it was a wonderful experience.

- Follow All Things Robert Dudley on WordPress.com

-

Out now! (U.K.)

Out Now! (U.S.A.)

You might also like … (U.K.)

You might also like … (U.S.A.)

Top Posts & Pages

- Did Good Queen Bess Kill More People for Religion than Bloody Mary?

- Jewels and ‟Such Other Pretty Stuff‟: Robert Dudley Goes Shopping

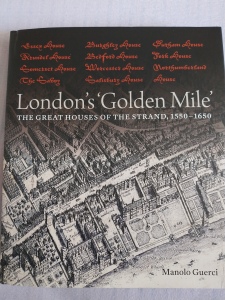

- Living on The Strand

- Did Henry FitzRoy and Edward VI Die of the Same Illness? Guest article by Sylvia Barbara Soberton

- The Green Parrot

- Family Relationships

- A Grand Conspiracy in 1553? – Foreign Affairs

- Letter to a Lady

- Robert Dudley's Noble Ancestors

- Who's Who?

Categories

1553 Ambrose Dudley Amy Robsart Andrew Dudley Douglas Sheffield Edmund Dudley Edward VI Elizabeth I errors & myths family & marriage friends & foes guest posts Guildford Dudley Henry VIII Jane Dudley John Dudley letters Lettice Knollys my books Netherlands paintings religion Robert Dudley Sir Robert Dudley sources & historians strange facts from popular booksTags

- ambassadors

- Anne Boleyn

- Anne Seymour

- Anthony Forster

- Archduke Charles

- Baron Dudley

- Bess of Hardwick

- birth date

- books

- Catherine de Medici

- Charles V

- Christopher Hatton

- clothes

- courtier

- Diego de Mendoza

- Dorothy Perrot

- Duke of Anjou

- Duke of Norfolk

- Duke of Somerset

- Duke of Suffolk

- Earl of Arundel

- Earl of Essex

- Earl of Huntingdon

- Earl of Oxford

- Earl of Pembroke

- Earl of Warwick

- education

- Elizabeth Grey

- Federico Zuccaro

- food

- France

- François de Scépeaux

- Garter

- health

- Henry Dudley

- Henry Sidney

- household

- Italian

- James Croft

- jewels

- John Appleyard

- John Gates

- John Hales

- Katherine Hastings

- Kenilworth

- Lady Jane Grey

- Leicester House

- Lord Denbigh

- Marquess of Northampton

- Mary Dudley

- Mary I

- Mary Queen of Scots

- Master of the Horse

- minority

- murder

- music

- Nicholas Hilliard

- Nicholas Throckmorton

- Order of St. Michael

- Penelope Rich

- Penshurst

- Philip II

- poison

- Prince of Orange

- Richard Verney

- Scotland

- Spanish

- Steven van der Meulen

- tennis

- Thomas Blount

- Thomas Darcy

- Thomas Seymour

- William Camden

- William Cecil

- William Paget

- My Tweets

-

Recent Posts

- Even More Blog Housekeeping

- Blog Housekeeping

- An Ox for the Earl of Leicester

- “I will put in the names” – Elections, 1584

- The Earl of Leicester’s Visit to the Town of Leicester

- Living on The Strand

- My Interview on the Dudley Family

- Lettice in the Theatre

- Lettice and Elizabeth

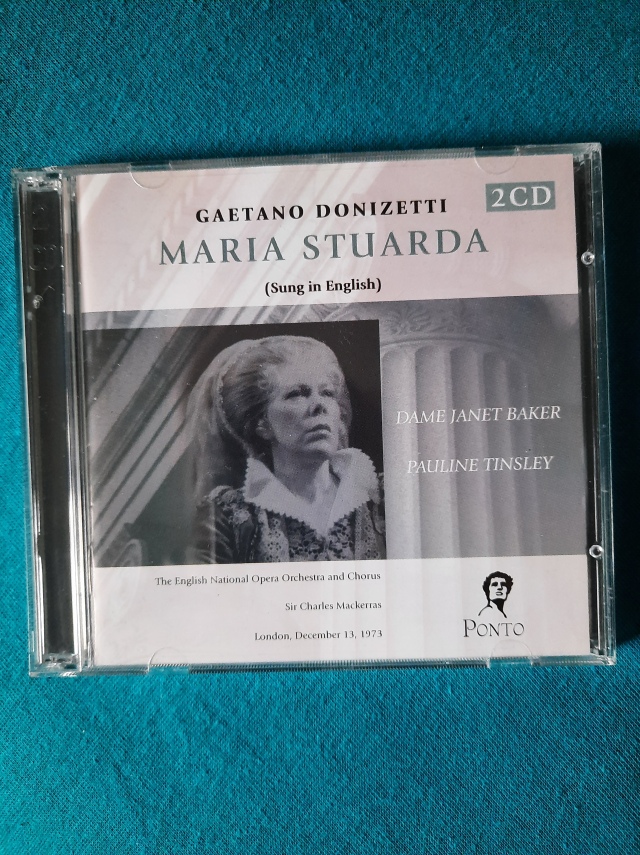

- Robert Dudley in Opera

- Banquet Massacres

- Mary Stuart’s M Necklaces

- Mary Stuart’s Open Ruff

- Smelling Wives?

- Did Henry FitzRoy and Edward VI Die of the Same Illness? Guest article by Sylvia Barbara Soberton

- Did Edward VI Tear Apart His Falcon?

- Some Portraits of Robert Dudley’s Siblings

- Robert Dudley in Quarantine

- Did Robert Dudley Send Money to Princess Elizabeth?

- The Portraits of Robert Dudley (5)

Archives

-

© 2011–2024 Christine Hartweg