The house was the grandest place in Cumnor, right at the centre of the village which had grown around this former summer retreat of the Abbots of Abingdon. Built around 1330 as a large quadrangle around two courtyards, it had undergone considerable alterations in the 15th century and by the late 1550s boasted a long gallery, the fashionable architectural element allowing people to stroll (and exercise) regardless of the weather. Probably in December 1559 Amy Dudley moved into the best chamber of Cumnor Place, a sumptuously furnished upper story apartment connected to a separate entrance with a staircase leading up to it. The room was lit by a large window in the late gothic style and would have been well-heated in winter. Not far away from her chamber was the great hall with its impressive, beautifully ornamented timber roof, and here the bustle of life in the house would have centered.

The building was owned by William Owen, who had inherited it from his father, the court physician Dr. George Owen, and had rented it to Sir Anthony Forster. A former Sherriff of Berkshire and Oxfordshire, Forster was a man of some standing and an established member of the Dudley affinity. He had administered the Duke of Northumberland’s principal estates in the Midlands1 and had handled important business transactions for Robert Dudley, involving thousands of pounds. Sir Anthony was certainly one of the men most trusted by his young master and friend.

Forster was a cultured man and talented musician2 and may have been responsible for the terraced pleasure garden at the rear of the house, which led to a large pond and a deer park of 25 acres. If, perhaps, Amy Dudley’s health did not permit her to hunt, she may at least have enjoyed the garden.

Apart from Sir Anthony Forster’s household and family, and Amy Dudley herself, two other ladies resided at Cumnor Place, the owner’s mother, Mrs. Anne Owen, and Mrs. Elizabeth Odingsells, a 41-year-old widow, who was related to the Owens by marriage. Like Amy with her own little entourage of some 10 persons, these two ladies would have employed their own servants, although probably less in number. Among Lady Dudley’s men were William Huggins, as well as three others “that wayteth upon my lady”, wearing a livery supplied by Lord Robert.3 Her maid was Mrs. Picto, who gave important testimony after Amy’s death; among other things it shows how devoted she was to her mistress.

As the wife of Lord Robert – the son of a duke (however disgraced) and the queen’s great favourite who socialized with visiting foreign princes – Lady Dudley was the person of the highest rank in the small world of Cumnor. She was doubtlessly of amiable character, but she was also a lady. A lady capable of lording (or ladying?) over other inhabitants of the house; on 8 September 1560 she famously insisted on having much of the house to herself:

she would not that day suffer one of her own sort to tarry at home, and was so earnest to have them gone to the fair, that with any of her own sort that made reason of tarrying at home she was very angry. And came to Mrs. Odingsells the widow, that lieth with Anthony Forster, who refused that day to go to the fair; and was very angry with her also. Because she said it was no day for gentlewomen to go in, but said the morrow was much better, and then she would go. Whereunto my Lady answered and said that she might choose and go at her pleasure: but all hers should go, and was very angry. They asked who should keep her company if all they went. She said Mrs. Owen should keep her company at dinner. The same tale doth Picto, who doth dearly love her, confirm.4

Although most members of the various households at Cumnor Place would presumably have taken their meals in the great hall, especially the servants, the ladies it seems dined much more comfortably in their chambers. From Mrs. Picto we know that Amy Dudley was a sincerely devout person who, at least towards the end of her life, prayed daily on her knees. She had grown up in and married into evangelical households and may have wished to attend services and sermons frequently. Cumnor Place had its own beautifully decorated chapel, though it is unlikely that it would still have been in use. Next door to Amy’s chamber was the Cumnor parish church of St. Michael’s, where she would have met other well-situated ladies and gentlemen. Of widows and spinsters there were, for example, Dorothy Buckner and Elizabeth Munlowe. The former’s lodgings were rich in carpets and cushions, and she was the proud owner of several gold rings.5

Lady Amy may, of course, have received visitors from further away than Cumnor and possibly would have made visits herself to friends residing not too far away; families like the Norris,6 who were to play an important part in the enquiries after her death and in her funeral. It is unlikely, however, that she embarked on more extensive travels while staying at Cumnor, as this would almost certainly have left some traces in her husband’s account books.

Some information about her spending on clothes can be gleaned from these – but it is important to keep in mind that she would have engaged in other activities as well, like needlework, playing games, and reading. She dressed well and from her tailor, William Edney, ordered many pieces of apparel needing things like “freeze and buckram for the ruffs and collars” and “silk to set on the lace”:

a round kirtle of russet wrought velvet with a fringe …

a loose gown of damask, laced all thick over the guard …

a cloth and an apron …; thin lace with pearls on each side [of] the edge …; silk to set it on …; pointing ribbon to the same …; lace to the top of the apron …; sarcenet to face it …

a petticoat of scarlet, with a broad guard of velvet, stitched with eight stitches …

a Spanish gown of russet damask …

a round kirtle of black velvet, cut all over and fringed …

a round kirtle, the forepart of velvet with a fringe of black silk and gold …

a Spanish gown of velvet, with a fringe of black silk and gold

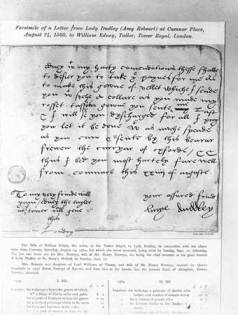

To her tailor she also addressed the second of her two surviving letters. It was found still in situ, pinned to Edney’s bill addressed “to my Lorde Robarte Dudles wyffe” which he sent to Lord Robert after Amy’s death. She wanted Edney to make some adjustments to a dress she had recently purchased from him:

Edney, with my hearty commendations this shall be to desire you to take the pains for me as to make this gown of velvet which I send you with such a collar as you made my russet taffeta gown you sent me last, & I will see you discharged for all. I pray you let it be done with as much speed as you can & sent by this bearer Frewen the carrier of Oxford, & thus I bid you most heartily farewell from Cumnor this 24th of August.

Your assured friend,

Amye Duddley7

continued from

A Favourite’s Wife: The Lifestyle of Amy Dudley, Part I

See also:

Before Elizabeth: Amy and Robert Dudley, 1532 – 1558

Notes

1 Wilson 2005 p. 247

2 Wilson 1981 p. 118

3 Skidmore 2010 p. 172

4 Skidmore 2010 pp. 381 – 382

5 Skidmore 2010 pp. 172 – 173

6 Wilson 1981 p. 118

7 Skidmore 2010 p. 192

Sources

Adams, Simon (1995) (ed.): Household Accounts and Disbursement Books of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, 1558–1561, 1584–1586. Cambridge University Press.

Girouard, Mark (1979): Life in the English Country House: A Social and Architectural History. BCA.

Jackson, J. E. (1878): “Amye Robsart”. The Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine. Volume XVII.

Owen, D. G. (1980) (ed.): Manuscripts of The Marquess of Bath, Volume V: Talbot, Dudley and Devereux Papers 1533–1659. Historical Manuscripts Commission. HMSO.

Skidmore, Chris (2010): Death and the Virgin: Elizabeth, Dudley and the Mysterious Fate of Amy Robsart. Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Wilson, Derek (1981): Sweet Robin: A Biography of Robert Dudley Earl of Leicester 1533–1588. Hamish Hamilton.

Wilson, Derek (2005): The Uncrowned Kings of England: The Black History of the Dudleys and the Tudor Throne. Carroll & Graf.